A few weeks ago, when I was reading “Gender Equality and State Environmentalism,” I noticed that Kari Norgaard and Richard York present an ecofeminist stance that I agree with and that I believe sums up how the oppression of women and the oppression of nature are interconnected expressions of patriarchal domination.

They believe there is “a link between gender equality and the environmental behavior of nation-states [as] implied by the assertion that sexism and environmental degradation reinforce one another” (510). From this theory, we are faced with a difficult truth: there is an inherent connection between the oppression of women and the oppression of nature, and it lies within the fact that the two are mutually reinforcing under perpetuated patriarchal hegemony.

It’s true that material deprivations and cultural losses of the marginalized and the poor lie within the deeper issues of disempowerment and environmental degradation because the oppression of these marginalized groups—whether they be women, the poor, nonhuman animals, the environment, or any other individual who doesn’t fall into the perpetuated Anglo-European androcentric and patriarchal mold—is tied to a logic of domination where men reinforce their own entitlement at the expense of all “others.”

We see this logic of domination in play when more and more mines are opened on Indigenous land, all for the profit and benefit of men and at the expense of the Native women and the environment within the area.

Legal research associate and activist, Julia Stern, explores this “Pipeline of Violence” in an Immigration and Human Rights Law Review blog post. She explains that “since the oil boom, Native communities have reported increased rates of human trafficking, sex trafficking, and missing and murdered Indigenous women in their communities.” Non-Native working men are coming in, appropriating land and contributing to ecological degradation in the process, and committing violent acts of oppression against the women they deem inferior because they truly believe they are entitled via their institutionalized logic of domination.

Furthermore, this logic of domination pervades and is enabled by all patriarchal societies. Capitalism and patriarchy and mutually reinforcing in the same way that the oppression of women and nature are mutually reinforcing. For both capitalism and the patriarchy, it all comes down to power—and power is money.

Just look at the literal rivers of trash degrading the Brazillian city of Recife. This photo of 9-year-old Paulo Henrique picking through the garbage-filled canal for aluminum cans to sell was published in the Journal de Commercio.

It’s not uncommon for Recife children to wade through filthy polluted water, through a filthy and polluted planet, for pocket change of the wealthy, but as VICE writer Talita Corrêa reports, “it was only after [this] image appeared in the press that the local government and international authoriries took notice…and promised to place Paulo, his mother, and his five siblings on welfare.”

It took bad press—a threat to the institution’s carefully crafted and projected image, ego, and capital—for any intervention or help to be offered. That’s because the institution is already aware of the oppression of both marginalized groups and nature and purposefully enables it. In fact, oppression is the instrument of the capitalist patriarchal institution’s domination as a means to keep the powerful wealthy and the wealthy powerful.

I’m sure it’s exhausting for you to read about all of this widespread domination, just as it’s exhausting for me to write about it. Just as it’s exhausting for those who experience it every day. And the worst part is, I haven’t even exhausted the examples. So, let’s keep going.

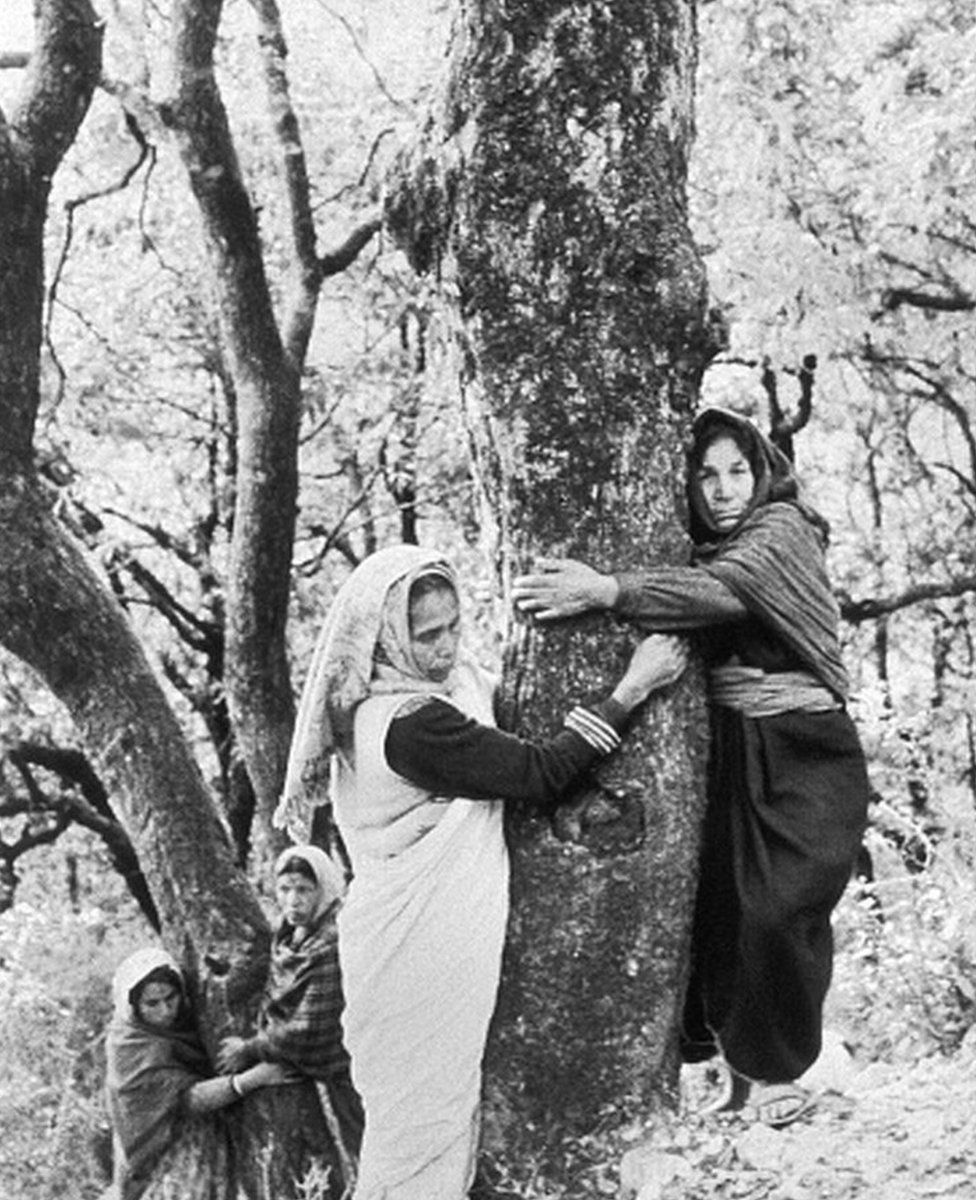

In India, the women-led Chipko movement was formed as a result of “the government’s decision to allot a plot of forest area in the Alaknada valley to a sports goods company. This angered the villagers because their similar demand to use wood for making agricultural tools had been earlier denied” (“The Chipko Movement”). Of course, the institution’s actions were a result of capital gain—it always comes back to money.

What’s even worse is the only way for the movement to make any real difference as far as environmental treaties are concerned was when a man entered the conversation and appealed to the institution’s greed. “Mr. Sunderial Bahuguna, a Gandhian activist and philosopher, whose appeal to Mrs. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India, resulted in the green-felling ban. Mr. Bahuguna coined the Chipko slogan: ‘ecology is permanent economy’ (“The Chipko Movement”). Even with a female Prime Minister, there’s no severing the innate connection between a capitalist patriarchal institution and an incentive toward capital.

We see it again in Kenyan activist and leader of The Green Belt Movement, Wangari Maathai, and her tumultuous path toward an ecofeminist future.

—

“Maathai won the Africa Prize for her work in preventing hunger and was heralded by the Kenyan government and controlled press as an exemplary citizen.

A few years later, when Maathai denounced President Daniel Arap Moi’s proposal to erect a sixty-two-story skyscraper in the middle of Nairobi’s largest park (graced by a four-story statue of Moi himself), officials warned her to curtail her criticism.

When she took her campaign public, she was visited by security forces. When she still refused to be silenced, she was subjected to a harassment campaign and threats. Members of parliament denounced Maathai, dismissing her organization as ‘a bunch of divorcees.’

The government-run newspaper questioned her sexual past, and police detained and interrogated her without ever pressing charges. Eventually, Moi was forced to forego the project, in large measure, because of the pressure Maathai successfully generated.

Years later, when she returned to the park to lead a rally on behalf of political prisoners, Maathai was hospitalized after pro-government thugs beat her and other women protesters” (Kennedy).

—

This woman braved a slander campaign that simultaneously disenfranchised herself, the other activist women, and the environment—all because of a powerful man’s ego and just entitled logic of domination. At this point, the pro-government thugs mentioned are synonymous with pro-privilege, pro-privilege that is afforded by institutionalized patriarchal hierarchies.

Or consider how the worst insult that President Moi’s campaigning could come up with was labeling the women “divorcees,” asserting the logic that a woman’s worth is freely given and revoked by a man. It’s a sign to other entitled, privileged men that these women’s husbands don’t value them, so why should any other man? This is a harmful, oppressive, and dominating logic to have, and yet it’s all around us.

Additionally, Maathai notes that “the men see trees as an economic investment. They look thirty years into the future and see that they will have huge trees to sell. Well, nevertheless, it means that The Green Belt Movement enjoys the participation of men, women, and children” (Maathai). Again, we see how consistently men only respond to economic growth because capital is power in our hierarchical system.

—————–

We’ve now traced the patriarchal logic of domination from America to Brazil to India to Kenya. The point is that it’s not a localized issue—it’s global. And while, yes, feminist and ecofeminist discourse is important to educate others and spark conversation toward an inclusive, intersectional, nonhierarchical future, it’s not nearly enough on its own to make a change.

In her article “Ecofeminist: A Latin American Perspective,” ecofeminist Ivone Gerbara reminds us, “While these discussions are going on, lots of women and children are starving and dying with diseases produced by a capitalist system able to destroy lives and keep profit for only a few. The challenging question…is not the struggle among different ways of interpreting women’s lives and the ecosystem, or the reductionism of theories, but the destruction of life while we are discussing the theories” (94-95).

Maathai emphasizes how “Environmental protection is not just about talking. It is also about action” (Maathai). But we cannot make a difference if we—all “others” in the eyes of patriarchal hegemony—are divided by trivialities.

What’s even more eye-opening is that we can’t just shift all of the blame either. Shifting the blame only fuels and justifies complacency. We can’t just point a finger at those in power and leave it at that.

Maathai has practice articulating this idea, so I’m going to share her analogy here. Maathai asks,

—

“‘Where do you think these problems come from?’

Some people blame the government, fingering the governor or the president or his ministers. Blame is placed on the side that has the power. The people do not think that they, themselves, may be contributing to the problem. So, we use the bus symbol…

If you go onto the wrong bus, you end up at the wrong destination. You may be very hungry because you do not have any money. You may, of course, be saved by the person you were going to visit, but you may also be arrested by the police for hanging around and looking like you are lost! You may be mugged—anything can happen to you!

We ask the people, ‘What could possibly make you get on the wrong bus? How can you walk into a bus station and instead of taking the right bus, take the wrong one?’

The most common reason for people to be on the wrong bus is that they do not know how to read and write. If you are afraid, you can get onto the wrong bus. If you are arrogant, if you think you know it all, you can easily make a mistake and get onto the wrong bus. If you are not mentally alert, not focused. [Or] Because the government was so oppressive, fear was instilled in us, and we very easily got onto the wrong bus. We made mistakes and created all of these problems for ourselves” (Maathai).

—

But what good is staying on that bus once you realize it’s the wrong one? Sure, staying on the bus is easy—it’s comfortable. You can point a finger to a million and two different external reasons why you’re headed in the wrong direction. But in the end, you’re still going to end up in the wrong place.

The only way to change the institutionalized direction is to take action.

Because the scary truth is that those with power, those with money, and those with privilege have the means to act swiftly and definitively when their power or capital is at risk, and upsetting their superior station in the hierarchy is the largest threat they could imagine.

I can’t stress this enough: Money Makes Moves. Money Motivates. Capitalist society will act and act quickly to make more or defend capital. When feminists and ecofeminists expend all their energy on discourse that divides and fragments their shared ideals—their power—they’re mutually reinforcing the oppression as well…they’re on the wrong bus. The only way to make a change is to unite the forces of all marginalized voices to topple the patriarchy that opposes us all.

So let’s stop all this talking. What are you going to do to resist mutually reinforcing oppression?

———————————————————————————————–

Works Cited:

“The Chipko Movement.” EduGreen, Teri, edugreen.teri.res.in/explore/forestry/chipko.htm.

Corrêa, Talita. “The Brazilian Slum Children Who Are Literally Swimming in Garbage.” VICE, 30 Jan. 2014, www.vice.com/en/article/kwpwja/the-brazilian-slum-children-who-are-literally-swimming-in-garbage-0000197-v21n1.

Gebara, Ivone. “ECOFEMINISM: A Latin American Perspective.” CrossCurrents, vol. 53, no. 1, 2003, pp. 93–103. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24461123. Accessed 1 Apr. 2023.

Norgaard, Kari, and Richard York. “Gender equality and state environmentalism.” Gender & Society 19.4 (2005): 506-522.

Stern, Julia. “Pipeline of Violence: The Oil Industry and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women: Immigration and Human Rights Law Review.” Immigration and Human Rights Law Review | The Blog, 24 May 2022, lawblogs.uc.edu/ihrlr/2021/05/28/pipeline-of-violence-the-oil-industry-and-missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women/.

Maathai, Wangari. “Speak Truth to Power.” Edited by Kerry Kennedy, The Green Belt Movement, 4 May 2000, http://www.greenbeltmovement.org/wangari-maathai/key-speeches-and-articles/speak-truth-to-power.

Hi Jasmine,

This was truly a captivating read and well written blog post discussing the connection between the oppression of women and the oppression of nature while highlighting the deeper issues of disempowerment under patriarchy and capitalism. I appreciated your opening in connecting us back to the work of Norgaard and York as the link between women representation and state environmentalism is supported throughout the movements of activism in which we analyzed in this week’s material. Drawing explicitly on your point about natural resources such as trees which sustain the life of those marginalized by power, it is crucial that you make the point, “Money Makes Move. Money Motivates.” In a nation that favors profit, power, and privilege over the adequate livelihood of all life across the natural world, this cannot be any truer. As the women of The Chipko Movement embraced the trees threatened with deforestation and the women of The Green Belt Movement planted seedlings into the ground degraded by capitalistic infrastructure, they were using their only ability of minimal yet powerful action to show trees are life, they are not to be monetary, and they are not to be objectified just as the lives of those disadvantaged at the hands of power. It should not be about capital gains, but the regaining of life that has continuously been destroyed because of the disconnect between humans and the natural world. The women of Somali society are an additional example of environmental activism. Like the women we have read about this week in India and Kenya, Somali has also fallen victim to the exploitation of the natural world as deforestation and desertification are main causes of environmental degradation. Shukri Haji Ismail Bandare explains, “The environment is the most essential necessity in our lives as we depend one hundred percent on it…These communities depend upon a healthy natural environment for their survival in the hot, dry climate with irregular rainfall” (Bandare and Jibrell 73). As those with power cut down the trees to make charcoal for profit, the vegetation in which the lands were once rich begins to disappear. Women who are most affected by these acts of degradation become involved in movements to end such oppression. Bandare states, “Women are intimately concerned with the changes in weather pattern and rainfall, they have to personally calculate how long to walk to get water, how far to take their herd for watering and pasture” (76). Like other women living in the Global South, destruction of the environment is an act of harm towards human life. Fatima Jibrell also of Somali society has united people and groups of women in advocating for an end to charcoal trade that has cut down the region’s supply of acacia trees for charcoal trading corporations to generate profit (74). Through movements to end such destruction, Fatima was able to develop an alternative to charcoal fuel with a solar powered cooker using her own ability and help of those impacted throughout the community. I include this example as an addition to your blog post as I believe it highlights the deeper issues behind cultural and material losses. The marginalized are not only losing natural resources and the sense of culture, but these acts of degradation are also rooted in disempowerment for those of lower social status. Somali is just one example of gender inequality that fails to hear the voice of women in policy-making decisions and as demonstrated in the example of Bandare, Jibrell, and all the other women-led activist movements, there is a need for women in representation to diminish the oppression of land and women. You leave the reader with an important call, the need to unite the forces of all those marginalized to deconstruct the patriarchy that works to keep the power in power while the powerless remain unheard. Women have taken action in ways that they can support their communities and land, imagine the leaps that can be made when given the opportunity to have their voices represented.

If you are interested in reading more of the piece I referenced on the environmental activism by women in Somali, here is the citation information: Bandare, Shukri Haji Ismail, and Fatima Jibrell. “Women, Conflict and the Environment in Somali Society.” Why Women Will Save the Planet, 2nd ed., Zed Books, London, UK, 2018, pp. 71–79.

Best,

Kylie Coutinho

Hi Jasmine,

I appreciated your informative blog post on this week’s topic. I found the manner in which you used all the readings to make an explicit call for action motivational.

When looking again at the topics of the Chipko and Green Belt movements as described in your post, I was struck by the different ways we amass knowledge and what we consider valuable knowledge. As you point out, in the Chipko Movement, the women in the Alakanada Valley had a knowledge of how the forests could sustain local construction of agricultural tools, healthy soil, and clean air and water. On the other hand, the government either did not have or did not value that knowledge. Instead, the knowledge of how to exploit those forests for capitalistic gain was valued when the sporting goods company was initially allotted use of that forest. When applying standpoint theory to this situation, the women in the Chipko Movement had a specific bank of knowledge of the environment partially because of their material realities influenced by class, gender, and location.

The Green Belt Movement also has connections to standpoint theory. The founder of the Green Belt Movement, Professor Wangari Maathai, had what could be described as an insider/outsider advantage. Originally from rural Kenya and having had many years of experience working with women in Kenya, Maathai had “insider” knowledge of the environment and its connection to women’s lives. However, Maathai also had “outsider” knowledge of the environment and social systems through experiences gained through academic degrees in the sciences from universities in Kansas, Pittsburgh, Germany, and Nairobi. Researcher Kristen Intemann emphasized the valuation of insider/outsider knowledge in standpoint theory when approaching scientific problems in a way that is more likely be socially responsive. For Intemann, looking at what we view as knowledge is an important aspect of centering and evaluating the needs of the marginalized (2015).

It seems clear that the way in which we “know” an issue or environment has a significant impact on our approach to issues. Looking at the social and environmental issues that the Chipko and Green Belt movements attempt to address also highlights the importance of re-examining what we view as valuable knowledge.

For more specifics on standpoint theory:

Intemann, K. (2015). “Feminist standpoint.” In Disch, L. & Hawkesworth, M. (Eds.) Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, (pp. 262-282). DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.14

Hi Jasmine,

I love BK’s art, and I am so happy Lizzy introduced us to it. It truly complements the posts so well!

Your post was insightful in how it brings attention to the widespread influence of patriarchy, and its ongoing reinforcement of a mindset of domination that results in the oppression of women, animals, and the natural world.

I especially enjoyed how you highlighted the mutually reinforcing nature of capitalism and patriarchy, where power and money are the ultimate drivers. It is important to recognize that these systems are interconnected and that any attempt to dismantle one must also address the other. The connection between capitalism and patriarchy is deeply rooted in the way both systems are built and operate; both are systems that prioritize the accumulation of power and wealth in the hands of a privileged few, at the expense of the marginalized and oppressed.

Both capitalism and patriarchy rely on the idea that power and wealth are finite resources that can only be controlled by a select few. This perpetuates a system of competition and scarcity, where individuals and groups are pitted against each other in the pursuit of power and resources. This competition is often most pronounced between marginalized groups, who are forced to compete for resources that are intentionally kept scarce by those in power.

In order to dismantle systems of oppression, we must recognize the interconnections between capitalism and patriarchy and work to address both simultaneously. This means challenging the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of a few and working towards a more equitable distribution of resources and opportunities.

I think Wangari Maathai’s experience is a clear example of how patriarchy and capitalism both operate in society. President Daniel Arap Moi’s proposal to build a skyscraper in Nairobi’s largest park was a clear display of patriarchal power and domination. By attempting to override the voices of those who opposed his plan, he was enforcing a patriarchal system that values the opinions of men over women.

The harassment campaign and threats that Maathai faced after she spoke out against the proposal illustrate the ways in which patriarchy seeks to silence women who dare to challenge its authority. By subjecting her to such harassment, President Moi and his supporters were attempting to intimidate her into silence and maintain their grip on power. But she refused to be silenced and was true to her mission until the very end, and in 1991 she won the Goldman Environmental Prize for her efforts.

If interested in learning more about the prize and watching a short video about how she became an environmentalist, see link below.

https://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/wangari-maathai/#recipient-bio